Paris de Noche. On “Paris Noche” at Night Gallery, Los Angeles

The protagonist of P.T. Anderson’s recent film adaptation of Thomas Pynchon’s novel Inherent Vice is an unremittingly stoned hippie who lives at the beach. “Flatland” is his term of derision for both the mindset of Los Angeles’ “respectable society” and the areas in which it is to be found. It is a term with meanings both geographical and conceptual. When he dismissively refers to someone as “a nice Flatland chick,” he refers to boundaries economic, social, and aesthetic, the difference between liberal and conservative, hip and square, idleness and industry. In truth, however, the opposition between beach and Flatland is not as clear as one might have it. The film depicts the hippy’s views as anachronistic, a product of his own sentimental longing for a better past.

The other characters in the film are less bound to old ways. They are introduced in geographically specific settings only to abruptly reappear elsewhere, out of their element. One character is first seen at a massage parlor in the South Bay, but later rematerializes at a mansion in Topanga, asking if she can bum a ride. Another, a front man for a surf rock band, is spotted at a Nixon rally. The incongruousness of these appearances, and others like it, hint at the theme of the film, which is traffic: not in the sense of gridlock, but in the sense of trade. Almost without exception, everyone in the film is looking for some opportunity for arbitrage, working the spread between two seemingly irreconcilable worlds. Characters slide from conservative to radical and back again. There are black militants collaborating with the Aryan Brotherhood, television hippies advertising condos to prospective hippy homeowners, and a drug runner’s front in the form of an Ojai rehab clinic. In the Los Angeles of Inherent Vice, there is no definitive “sell-out,” only a daily grind of discerning and contextualizing difference. As if to symbolize this, Anderson has placed a recurring motif or emblem in the background of multiple scenes: a profile view of a smuggler’s schooner.

“Paris de Noche,” a three-person show at Night Gallery, with work by Andrei Koschmieder, Pentti Monkkonen and Amy Yao, features a series of wall reliefs by Monkkonen that might be compared to the schooner in Inherent Vice. In each relief, Monkkonen depicts a white cargo truck in two dimensions, reducing the white cuboid volume of the truck’s cargo area to a flat panel made of cast plastic and cleverly selected off the shelf bits and pieces. Suggestive of an approach akin to that of some postmodern architecture’s reduction of form into sign, Monkkonen’s work translates the familiar vehicles into generic marquees. Each piece is then further stylized with a palimpsest of subcultural accents: the trucks’ cabs are shaped like skulls reminiscent of custom hot-rods, while their cargo areas are variously tagged with a sort of scaled down, dollhouse graffiti. With these additions, the vehicles become badge-like tokens of identity, like Harley Davidson key chains or refrigerator magnets.

Ironically, the temptation to read the box trucks as badges lies in their ambiguity. One is compelled to find an interpretation for the coexistence of identities found in the trucks. In smaller scale, the box trucks could hang from the rear-view mirror of the art handlers who crated and trucked “Paris de Noche.” They could also be read as an emblem for the young artist, whose work is shuttled around from ship to plane to truck before landing on temporary white walls in the gallery. Then again, perhaps the point of pride is not the truck itself but the graffiti throw-ups that Monkkonen has here carefully reproduced in miniature. When taken as a whole, the work suggests that it might represent any one, or all three, of the above; that in the present zeitgeist, one might readily imagine someone who has inhabited all of these identities, whether at various points in their life or even at the same time.

In addition to the box truck works, “Paris de Noche” features a second series of wall-reliefs, also by Monkkonen, based on building facades. Here, as with the box trucks, a cubic form is represented as a flat panel. The referent in this case is a blocky urban townhouse or luxury apartment, the kind of structure recently built by the dozens in the Mitte district of Berlin. Filling every interstice of open land, the facades are chillingly lacking in life: one is never really sure if they are occupied or still for sale. In his version, Monkkonen miniaturizes these facades, then complicates them by grafting their dead surface on to to the bone structure of Café de l’Enfer, a Belle Epoque bar and cabaret themed around hell, whose arched entrance was sculpted to resemble the gaping maul of a devil.

There is an undeniable similarity between the two architectures: the typical high ceilings, narrow profile and one car garage of the multistory Euro-loft almost perfectly overlays the face of the Café de l’Enfer’s wide-jawed Satan. Monkkonen crossbreeds the vertical slit window that would, for the apartment, fashionably reveal the interior rise of a staircase, with the bulging eyes of the defunct cabaret to yield effeminate, almond shaped lunettes. Instead of pupils, these eye-windows feature security grills (surely bespoke recreations of nineteenth-century iron work) and lace curtains. From the typically Parisian Art Nouveau house number panels, one can infer the street address of these genetic monstrosities: Rue Michael Jackson 1-3.

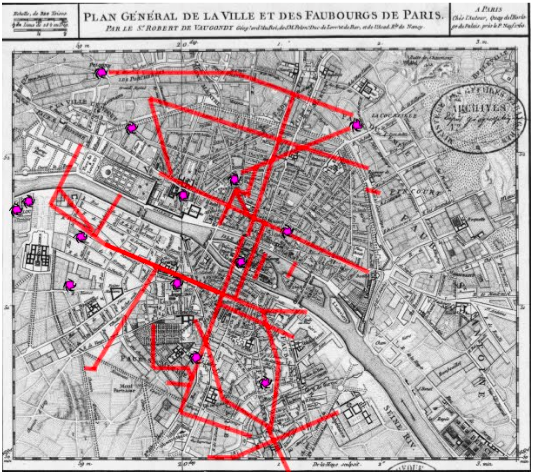

What is most persuasive about the facade works is not that they might, in their depiction of ostentatiousness and theatricality, literally or metaphorically represent a specific place. Rather, it is that they mimetically refer to the process of interpreting meaning in a building’s location and architecture. It is as if Monkkonen’s work demands that the viewer exercise their competency in evaluating real estate, alongside painting and sculpture. This makes the work especially timely in Los Angeles, where several galleries from New York and Europe have recently chosen to open new buildings, and where there has also been a spate of recent inaugurations of less commercial galleries and project spaces. In the press release for “Paris de Noche,” Monkkonen explicitly refers to Baron Haussmann’s restructuring of Paris, but the show’s subtext remains closer to home.

Whereas galleries in Los Angeles have tended until now to cluster in enclaves such as West Hollywood, Culver City, or Chinatown, the new galleries and project spaces are instead choosing locations dispersed throughout the city. Highly self-aware of the social and cultural connotations of their chosen geographic locations, they are also conscious of the semantic role played by location in the definition of their own identities. Real estate, instead of being an implicit or unspoken field of meaning, here becomes an overt aesthetic signifier. Although architecture and locale have traditionally been used as signifiers of prestige and economic success, the near-simultaneous arrival of several new galleries dramatizes and makes explicit the quasi-conceptual character of their choice of building and location. One can clearly perceive the galleries’ desire to differentiate themselves from one another as they triangulate within a structured field of strategic possibilities. The result is that the specific social relationships of the insular field of art are projected onto the vast and more general social and cultural terrain of the city. Furthermore, although the new galleries and projects are extremely disparate in scale, ambition, and means—from massive redevelopment projects in which entire city blocks are transformed into private culture complexes, to the repurposing of a modernist bank building, to young startup galleries in Hollywood retail spaces—all follow the common logic of using architecture and location to encapsulate their project’s artistic program and objectives.

The Haussmannization relevant to “Paris de Noche” is not that of the boulevard, which in its time enabled the circulation of economic and military power, but GPS and peer-to-peer car services. The art spectator or participant uses these tools to freely design a trajectory from one gallery to the next. Seeing a show or one’s colleagues implies the ability to travel unimpeded in the virtual field mapped over the city. If there is a shift in one’s attitude or preferences, one can effortlessly and immediately change one’s trajectory. In this abstract space, spatial relations become metaphorical. For gallerist and spectator alike, the virtual geography of the city is malleable. It can be read and altered in a signifying game whose parameters create categories and definitions, oppositions and mutual sympathies.

One prominent example of this phenomenon is Paramount Ranch, Los Angeles’ newest art fair, which is also organized by Monkkonen, together with Liz Craft, Alex Freedman and Robbie Fitzpatrick. The fair takes its name from the western town studio back lot in Malibu where it takes place. Instead of trade show booths, exhibitors operate businesses along the unpaved drag of a mock frontier town: the saloon, the undertaker, the stables. But even as the event enjoys a goofy costume party spirit, like a weekend spent on the set of Paul Morrissey’s Lonesome Cowboys, Paramount Ranch is also clinically precise in its positioning. The fair is scheduled to coincide with three other art fairs in Los Angeles, and it both benefits from, and contributes to the influx of out-of-town visitors. At the same time, Paramount Ranch’s western theme and location keeps it spatially and conceptually distinct from the others. Its location in Agoura Hills—twenty miles from Santa Monica and forty miles from downtown Los Angeles—underlines the emerging status of the fair’s exhibitors. In a deft balancing act, the fair represents untapped potential in a new frontier of artistic capital while remaining comfortably within reach, even for an out-of-towner in a rental car.

If one were to compare the geographic displacement of Paramount Ranch to the more extreme displacements of Land art of the 1960s and 1970s, one might conclude that the difference is one of relative versus absolute remoteness. Land art dovetailed with both the countercultural ideology of a retreat into nature and the European avant-garde’s romance with the landscape of the American West. The adherents of Land art understood their choosing remote locations as a clear repudiation of the art world’s geographic center and thereby its practices and principles. Even as a spectator of the work, one has to commit to being absent. Communication is broken by interruptions in cell signal; social occasions are replaced by roadside meals taken in solitude. The art insists that to see it one must drop out, at least temporarily. By contrast, Paramount Ranch is “far,” but only relative to the typical half hour drive between other points in Los Angeles. The simulated ghost town’s dirt road and dusty wooden porches were intended for the camera—it is remoteness only as depicted. The art on display—it’s an art fair, after all—has little aspiration toward the kind of defiant intransigence implied by, to take an example, Nancy Holt’s decision to situate Sun Tunnels in northwest Utah. While the work in Paramount Ranch does often have a kind of critical quality, it is reactive, and well calibrated, residing strictly on the grid.

This is not to say that Paramount Ranch is flawed in its accessibility. The fair finds its coherence in its pragmatism, showing a self-aware perspicacity for the limits of contemporary art. In Monkkonen’s relief works, however, this self-awareness is tinged with tragic overtones. In representing the structural traits of its context, the work resorts to macabre imagery, giving one the sense that pragmatism may come with unnamable consequences. When the hippy hero of Inherent Vice assumes a false identity to meet a wealthy matron, a developer’s wife, he mimics the requisite look; he puts on his version of a tie, and slicks back his hair to match his costume. Yet he can do nothing to conceal his oversize sideburns. The running gag in the film is that although he is able to sneak into the most disparate orders of society, he is in fact fooling no one.

From left to right : Amy Yao, Pentti Monkkonen