On Tobias Kaspar at kim? Contemporary Art Centre, Riga

When introduced to a selection of photos of works by Tobias Kaspar, a Moscow friend quickly and unequivocally labeled the art as “European,” implying that it was largely derived from a specific way of life and fitted squarely into it: art as a lifestyle brand, so to speak. Referring, among other things, to the artist’s recognizable motifs such as diverse tools of the fashion industry and consumer goods presented as status symbols, my friend felt the art was preoccupied with dispensable issues at the expense of its essential qualities and was dissatisfied with the lack of artistic volition to transcend the trivial. If only by the hasty dismissal, this commentary nevertheless grasped Kaspar’s objectives neatly. The artist refuses to internalize the existing mental schemata, which enables a steady functioning of any knowledge-based economy, e.g., fine art, and are often taken for essential statements. Instead he launches a set of operations to repel meaning as pre-given and immanent (thus the formally constructed dimension of depth is absent and indeed the art may appear superficial) and addresses how meaning works in mysterious ways, relying on the conviction that it is highly conditional.

The exhibition at kim? gave a perfect introduction to Kaspar’s practice and featured new works from 2017 that further develop his main interests—the production and distribution of culture and professionalization of daily life and socializing—in a loosely organized two-room installation somewhere between a small museum retrospective, a casual interior-like environment, and due to the diversity of discrete media, even a group show. People who provided technical assistance were mentioned in an accompanying text, reaffirming the artist’s manifest understanding of art as a collective effort by default. No wonder Kaspar’s operating mode emulates that of different supra-individual entities, e.g., a branding agency, a fashion house, or a community centre. Also adopted is their way to address, or rather target, the audience as a group: his pieces are designed to activate a viewer’s sense of (non-)belonging. Finally, the output itself anticipates possible modes of its distribution; it is often organized in a series, thus open to further thematic and site-specific adaptation and pre-packed as generic exhibition formats, which compress both historic and economic aspects of art into expected and viewer-friendly solutions (distantly reminiscent of Allan McCollum’s surrogates). As a result, the artist steps out of the fixed position of an individual artist appealing to a personalized viewer via a one-of-a-kind artifact. By downplaying individualism, the space is freed up for a more accurate and sobering view of discriminative dynamics in the cultural field. Involvement in it suggests a balancing of friendliness and acceptance, exaggerated in the show as literal hospitality through the addition of a sloping ramp at the entrance to the second gallery and two armchairs supplied with plaids, against rejection and indifference. The latter were hinted at by inexplicable signs and letters (full and partial logos of sites and products starring in the show) dotting the walls and a portal between the galleries made of printing plates for Kaspar’s book New Address (2017) featuring vague images of the artist’s friends’ faces—such polyphony of casual name-dropping merged in a mute hum that triggered awareness of being present as witness at the site of perpetual negotiating of various “us” versus “them” and “in” versus “out” configurations. The effect was planned to be rather chilling, or so it seemed due to the abundance of reflective and white surfaces: in particular, a brand-new fridge combined with an equally-shaped cube covered with fresh flowers.

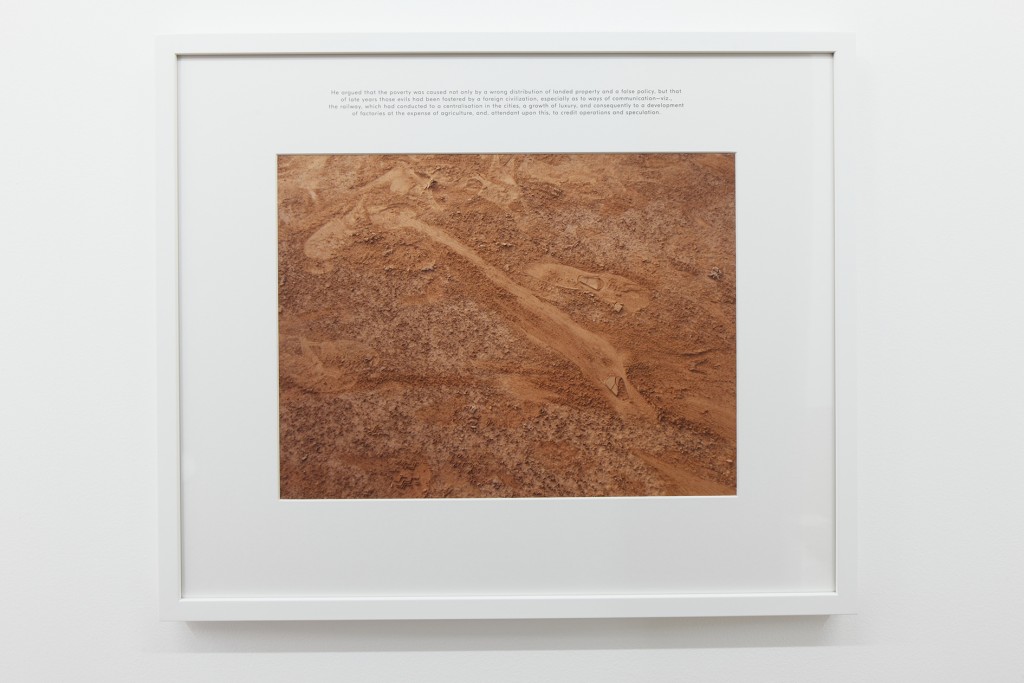

Tobias Kaspar, Anna K., 2017, inkjet print photographs with text print on matt board, 26.8 x 22.4 x 1.2 in.

Typical sculpture surrogates by Tobias Kaspar feature casts of prosthetic items, shoes, and bottled liquids, and chronicle people’s attempts to grasp at least something in a flux of substitutes of a meaningful life. These objects embody otherwise intangible tectonics of social stratification. As intermediaries in daily socialization, they are chosen by Kaspar to either trumpet the urgency of a frontier moment of establishing what is important or testify to the glorious struggles for recognition of the past. Samples on view in the show included Dr. Martens 1460 boots, both shoes of a pair cut in half to reveal the solemn glow of polished bronze worthy of a trophy, and porcelain casts of bottles of bath and body products as part of a scatter installation. Then there were panels of stretched reflective fabrics with rectilinear grid patterns laser-cut onto it. Hung tightly side-by-side next to two armchairs and a carpet littered with bottles and tubes, plastic wrapping, notepads, and boxes, as if extras in a family drama-commercial crossover, they thoroughly documented the movement of a certain material from one industrial context to another (safety—fashion—fine art) and the gradual extraction of different utility aspects of it. Finally, an entire wall was occupied by a photo series, circling obsessively around a single subordinate subject with texts printed on matt board, a format frequented by Kaspar. It featured close-up shots of slightly unkept and empty tennis courts in Riga and Rome with quotes from Leo Tolstoy’s novel Anna Karenina (first published as a book in 1878) in Russian, English, and Latvian, one language per photo. The accessibility of content alternated with a sense of puzzlement, attesting to the key importance of translation for meaning-making. One particular image was cropped in such a way that only a rectangle of an ocher Martian-like soil with traces of indistinct activity was visible, reminiscent of a common figure present in fine art for some time already. Featuring an unmanned terrain, often extraterrestrial, such works relativize subjective human experience, as structured linguistically, and celebrate the ecology of nonhuman actors and processes in order to reconstruct the possibility of meaning on another solid ground. The photograph appeared to me as a sly disapproval of this neo-futuritic revival of an age-old attempt to bewitch reality into a set of fixed forms. An added polemical fragment from the novel on the challenges of city growth and industrialization yielded a sense of the datedness and futility of a tradition of theorizing, which engages technology and natural sciences. The photograph appeared to me as a sly disapproval of a current neo-futuristic revival of an age-old attempt to bewitch reality into a set of fixed forms. Mixing small talk and project-mongering with distracting imagery, Kaspar presented the generalized manner in which arguments are conducted in the current blend of theory and edutainment augmented by social networks. The apparent obsession with the next big idea, triggered by the anxiety of a hands-on approach, was counter-balanced by a humble humanism; deliberately selected mentions of baby care, food preparation, and walking—and more ironically, playing tennis—seemed to praise the wisdom of daily life also felt in other exhibitions around.

The accompanying text presented the photo series and entire installation as a development of the modern literary and fine art tradition of “object portraits.” Indeed, upon entering the homey environment built by Kaspar, one might start a three bears’ enquiry into who sat in this armchair, who applied those lotions, who wore Dr. Martens, and even who rereads Tolstoy nowadays, with a vague imagined character eventually appearing (scamming the game would be of course to identify the subject as the artist himself directly). Although the show updated Tolstoy’s list of changes brought by modern life, and now including sports, gentrification, and contemporary art itself, the result was less a coherent figure of a witness and arbitrator of modernization supposed by the novel’s main character; it was exactly Anna K. (the title of the photo series), a disembodied avatar. In one sense, it masked the failure of modernization felt in the melancholia of everyday life, which was constructed in the installation via a range of metaphors and materials, such as dull shades of red, pallid ceramic vessels (funeral urns), lazy paintings which only showed something occasionally, shabby tennis courts devoid of action—this anemic state alluded to the disbelief in political action shared by many. In another sense, it linked the polyphony of multiple profiles of cultural producers and consumers under a female moniker (as became common in the fine art economy of recent decades, e.g., Reena Spaulings). Or, alternatively, it didn’t abuse the instinct of identifying oneself with an animated entity altogether—instead it involved the viewer’s analytical and imaginative capacity by unfolding a flow of matter and information. Rich in associations, the installation doubled as a condensed narrative of art history. Running parallel to the show’s theme of historical modernization, it featured multiple ways to process meaning, e.g., concrete poetry in deconstructed logos, a scattered installation with shopping bags, carpet and seats not unlike those made by Sylvie Fleury, and a site-specific furniture sculpture in a form of a worker’s locker reflexive of kim?’s factory past. The diversified amorphism of the installation became its virtue. The lack of a unifying momentum inside, neither as individualism of traditional modern art, nor as animism of post-human tableaus, left viewers free to make sense on their own.